Geospatial Data Orchestration: Why Modern GIS Pipelines Require an Asset-Based Approach

In the world of data, true turning points are rare—moments when a technology originally designed for one category of problems turns out to be the missing piece in a completely different domain. This is precisely what is happening now in geospatial data. Workflows traditionally rooted in the GIS niche have become one of the most demanding components of contemporary AI systems and environmental analytics.

What once relied on manual work inside desktop tools must now meet requirements of scalability, reproducibility, and full automation. Models need to be retrained continuously, data arrives in real time, and every forecast must be explainable and fully reproducible.

These were exactly the challenges we faced while building a cloud-native hydrological and environmental data processing system — one that merges dynamic measurements, large raster datasets, machine learning, and GIS-based interpretation. That experience made one thing very clear: geospatial does not simply need “better workflows.” It needs an orchestration layer that treats data as the primary actor — not a byproduct.

Dagster became the natural choice for such an architecture. Dagster is increasingly used for geospatial data orchestration because its asset-based model aligns naturally with GIS datasets, raster processing pipelines, and reproducible environmental analytics.

What is geospatial data orchestration?

Geospatial data orchestration is the practice of managing, automating, and governing complex GIS and spatial data pipelines — including raster processing, feature engineering, machine learning training, and data publication — in a way that is scalable, reproducible, and fully traceable.

Unlike traditional GIS workflows that rely on manual execution inside desktop tools, geospatial orchestration treats datasets and derived artefacts as first-class assets with explicit dependencies, versioning, and lineage.

Why asset-based orchestration is the language geospatial systems speak intuitively

In geospatial projects, every element of the workflow — an elevation raster, a land-cover classification, a soil map, a catchment-level aggregation, a training tensor — exists as a meaningful artefact with its own purpose and lineage. These artefacts form the narrative spine of the entire system.

While building the hydrological platform, we quickly discovered that geospatial processing fundamentally conflicts with the task-oriented paradigm used by most workflow tools. In hydrology, meteorology, or environmental modelling, “a task” is merely a transient carrier of work. What matters is the end product: the raster, the derived feature set, the trained model, the forecast.

This is precisely why Dagster’s model — where the core unit is the asset, not the task — feels almost native to geospatial data.

When we convert a DEM to a tile-optimized raster format, we create an asset.

When we generate soil attributes or retention-capacity parameters for a catchment, we create assets.

When we produce features for training a model or build the final forecasts — those are assets as well.

Each of these objects has a life of its own, a history, and a network of dependencies. Dagster makes this structure visible, not as an incidental side effect of code, but as the logical architecture of the entire system.

Why traditional workflow orchestrators struggle with geospatial pipelines

Most workflow orchestrators were designed for task-centric ETL pipelines. In geospatial systems, this approach breaks down because tasks are transient, while spatial datasets — rasters, tiles, features, and models — are long-lived analytical artefacts.

As a result, task-based orchestration makes lineage harder to understand, reproducibility fragile, and debugging costly in GIS-heavy and environmental data pipelines.

In geospatial, transparency is not a nice-to-have — it is a necessity

One of the core lessons from developing environmental systems is simple: results must be explainable. A hydrologist, GIS analyst, or decision-maker responsible for assessing risk must understand where every value in the model comes from and what transformations shaped it.

The orchestration we implemented enforces this clarity. Every stage — from data ingestion, through raster processing, to modelling and publication — leaves behind a durable artefact. There are no hidden transformations, no opaque steps, no “magic.” If a forecast changes from one iteration to another, we can point to the reason. If an experiment needs to be repeated, we do it deterministically.

Dagster amplifies this transparency, because it expresses the system as a web of dependencies between artefacts. In the geospatial architecture we built, full lineage is visible: from raw rasters to intermediate steps to the final products consumed in QGIS. This is not optional — it is a foundational requirement for analytical responsibility.

The cloud removes infrastructure friction; Dagster gives the system its rhythm

Geospatial data is large, and its processing can be computationally intensive. That is why one of the priorities of our solution was to clearly separate data processing from the infrastructure that executes it.

A central object store in S3, container-based processing, demand-driven autoscaling, version control of experiments in MLflow, and a permanent division between ETL and model-training environments allowed us to simplify the entire ecosystem. The team could focus on data, not on the platform itself.

Dagster acted as the coordinator in this architecture. It defined the relationships between artefacts, governed how data was refreshed, and set the cadence for model training. It provided structure without imposing unnecessary constraints, enabling architectural decisions to be made at the level of data — not infrastructure.

This is one of the benefits that only becomes visible in large geospatial systems: orchestration should not be a heavyweight layer “on top” of the system but a lightweight skeleton on which the system naturally rests.

Engineered for elasticity: The physical architecture

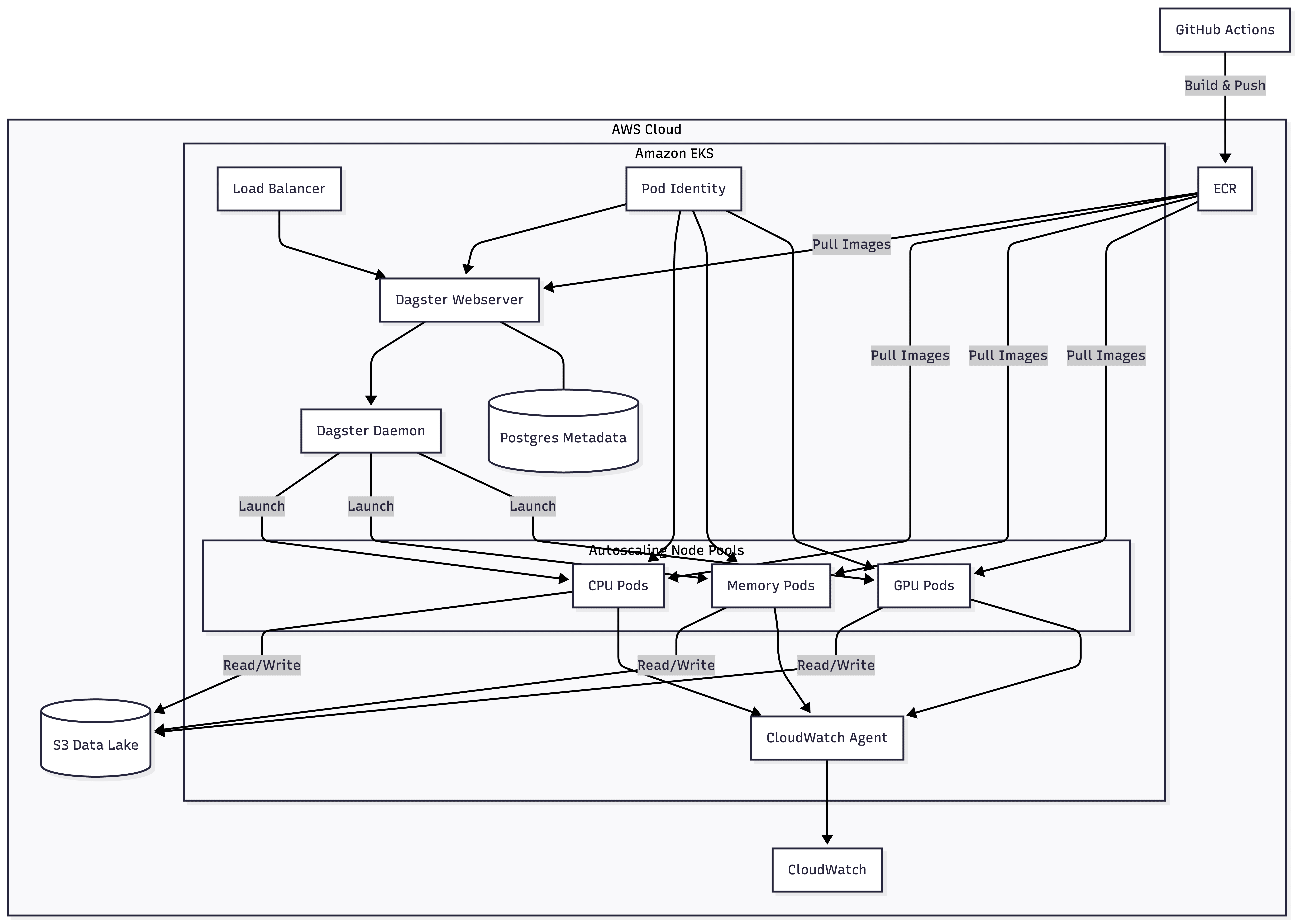

Our implementation relies on AWS EKS to absorb the extreme variance in geospatial compute. We treat infrastructure as elastic capacity, not a fixed cluster: it expands and contracts in response to the asset graph.

The cluster is divided into specialized node pools. Core services run on steady instances, while processing tasks route to autoscaling groups sized for their load — from lightweight CPU jobs to memory‑heavy raster operations. For machine learning, GPU nodes are provisioned on demand; a Dagster asset declares its needs via tags, and the cluster autoscaler supplies them. We pay for high‑performance compute only during the minutes that model training runs.

Operational rigor comes from isolation and clear identity boundaries. We split the Dagster deployment into two code locations — Data Preparation and Machine Learning — because geospatial stacks like GDAL and Rasterio conflict with the numerical stacks behind PyTorch or TensorFlow. Collapsing them into one environment creates brittle builds and version lock. By keeping them separate, each location owns its dependencies, and Dagster orchestrates across the seam cleanly. Security uses AWS Pod Identity to avoid long‑lived credentials, and GitHub Actions maintains a clean lineage from commit to ECR images. CloudWatch then provides a unified view of infrastructure health and pipeline performance.

This architecture delivers elasticity as a daily operational fact. After a training run, GPU nodes drain and terminate within minutes, returning spend to baseline. When a large raster arrives, the relevant pool expands to meet it, then contracts once the asset materializes. The system breathes with the workload — responsive at peaks, economical in troughs — without manual intervention or capacity planning. Most importantly, infrastructure fades from view: an asset definition states what it needs, and the platform ensures those resources appear exactly when required.

GIS remains a first-class partner, not collateral damage of modernization

Many contemporary data platforms try to replace GIS with proprietary viewers or dashboards. Yet in practice — and especially in environmental and hydrological projects — GIS tools remain irreplaceable. In our approach, GIS is not a competitor to modern data architecture but its natural consumer.

Final datasets are exposed in formats analysts know: GeoTIFF or Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF. As a result, GIS becomes a direct extension of the orchestration layer. Dagster produces the data; GIS interprets it. This separation of roles not only simplifies the system but also increases acceptance among experts who rely on these outputs daily.

Business value emerges not from automation, but from reduced analytical risk

From a technological standpoint, Dagster streamlines the workflow.

From a business standpoint, it does something more important: it reduces operational and analytical risk, which in geospatial projects is distributed across data quality, model correctness, and the reliability of forecasts used in decision-making.

In the architecture we built, every decision about data is reflected in the structure of artefacts. Every change is visible. Every experiment is reproducible. This means more control, less uncertainty, and a system that is significantly more resilient to errors and shifts in external conditions.

That is why well-designed orchestration becomes a strategic component — not an accessory — in geospatial data platforms. In domains where forecasts influence infrastructure planning, risk mitigation, or public safety, this level of analytical control is not a technical luxury — it is an operational requirement.

Frequently asked questions

Is Dagster suitable for geospatial and GIS workloads?

Yes. Dagster’s asset-based orchestration model works particularly well with geospatial pipelines where rasters, features, and models must be versioned, traced, and recomputed deterministically.

How does geospatial orchestration differ from traditional ETL?

Geospatial orchestration focuses on managing spatial data artefacts and their lineage rather than executing isolated tasks. The goal is analytical transparency and reproducibility, not just automation.

Can cloud-native orchestration coexist with GIS tools like QGIS?

Yes. Orchestrated pipelines can publish standard formats such as GeoTIFF or Cloud Optimized GeoTIFF, allowing GIS tools to remain first-class consumers of cloud-native data platforms.

Conclusion: Geospatial is entering the era of orchestration — and Dagster is its natural foundation

Geospatial data has a unique character: it blends the physical world with the mathematical complexity of models and the interpretability of spatial visualization. When these three worlds meet in a single project, traditional approaches to data processing quickly show their limits.

Dagster, applied to geospatial systems, breaks through these limits. It enables an architecture in which large environmental datasets, machine learning models, and GIS-based analytics do not fight for dominance but coexist within a coherent ecosystem.

It is not a tool that promises magic. It offers something more valuable: clarity, reproducibility, and accountability.

This is why geospatial is increasingly gravitating toward orchestration.

And why Dagster, with its asset-oriented philosophy, is emerging as the most natural language for that transformation.