Architecting and Operating Geospatial Workflows with Dagster

This article is a technical companion to our earlier essay on geospatial data orchestration (link: https://u11d.com/blog/geospatial-data-orchestration/).

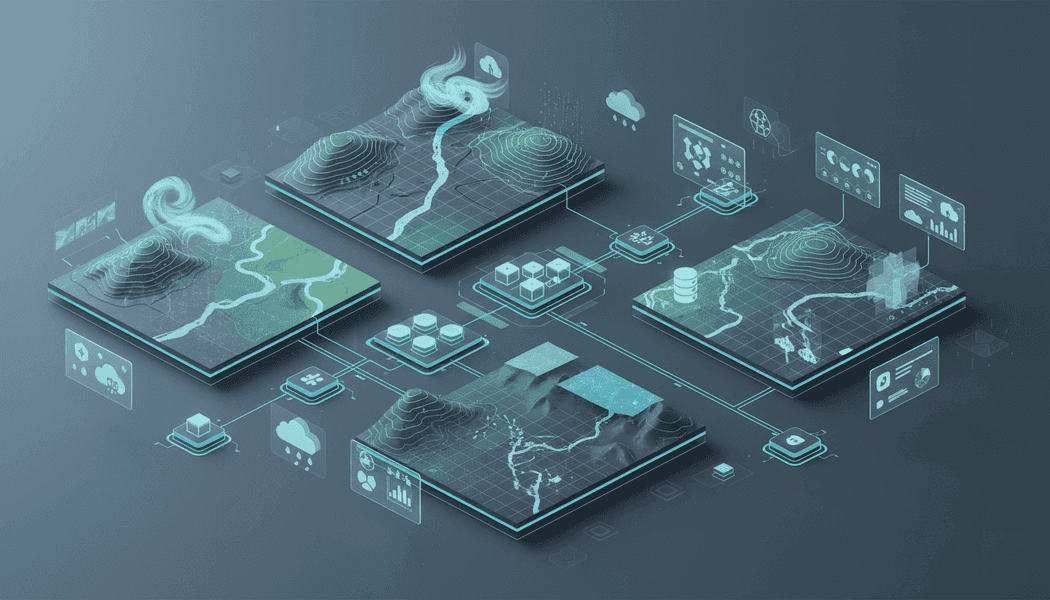

Geospatial data pipelines present a distinct set of challenges that traditional ETL frameworks struggle to address. Raster datasets measured in gigabytes, coordinate reference system transformations, temporal partitioning across decades of observations, and the need for reproducible lineage across every derived artifact-these requirements demand an orchestration model that treats data as the primary actor rather than a byproduct of task execution. This article describes the architecture we developed for water management analytics: a system that ingests elevation models, meteorological observations, satellite imagery, and forecast data to support flood prediction and hydrological modeling.

The System Boundary

The platform serves as a data preparation layer, not a model serving infrastructure. Its responsibility begins at external data sources-WFS endpoints, FTP servers, governmental APIs-and ends at materialized artifacts in object storage ready for consumption by downstream ML training pipelines and QGIS-based analysts. We deliberately exclude real-time inference, user-facing APIs, and visualization from this system's scope.

Two Dagster projects comprise the workspace. The landing-zone project handles all data ingestion and transformation: elevation tiles, meteorological station observations, satellite imagery, climatic indices, and forecast GRIB files. The discharge-model project consumes these prepared datasets to train neural network models for water discharge prediction using NeuralHydrology. Both projects share a common library under shared/ containing IO managers, resource definitions, helper utilities, and cross-project asset references.

The platform does not manage model deployment, handle user authentication, or serve predictions. Those responsibilities belong to separate systems that consume our outputs via S3-compatible object storage.

Data Types and Access Patterns

Three fundamental data types flow through the system, each with distinct storage and access characteristics.

Raster data-digital elevation models, satellite imagery, land cover maps-dominates storage volume. We store all rasters as Cloud Optimized GeoTIFFs (COGs) in S3, enabling range-request access for partial reads. The elevation pipeline alone processes tiles from multiple national geodetic services, converting formats like ARC/INFO ASCII Grid and XYZ point clouds into standardized COGs with consistent coordinate reference systems. A single consolidated elevation model can exceed several gigabytes.

Tabular data encompasses meteorological observations, hydrological measurements, station metadata, and computed indices. We standardize on Parquet with zstd compression, leveraging Polars for in-process transformations and DuckDB for SQL-based quality checks. A custom IO manager handles serialization of both raw DataFrames and Pydantic model collections, automatically recording row counts and column schemas as Dagster metadata.

Vector data-catchment boundaries, station locations, regional polygons-exists primarily as intermediate artifacts used for spatial joins and raster clipping operations. Shapely geometries serialize alongside tabular records in Parquet files, with coordinate transformations handled through pyproj.

All data resides in S3-compatible object storage. The storage layout follows a predictable convention: s3://{bucket}/{asset-path}/{partition-keys}/filename.{ext}, where asset paths derive directly from Dagster asset keys. This enables both programmatic access through IO managers and ad-hoc exploration via S3 browsers.

Asset Graph Design

Every durable artifact in the system maps to a Dagster asset. This is not a philosophical preference but a practical requirement: when a hydrologist questions why a model prediction differs from last month's, we need to trace backward through the exact elevation tiles, meteorological observations, and climatic indices that produced those training features.

Asset naming follows a hierarchical convention reflecting data lineage. Elevation data progresses through elevation/dtm/wfs_index → elevation/dtm/raw_tiles → elevation/dtm/converted_tiles → elevation/dtm/consolidated. Each stage represents a distinct, independently materializable artifact with its own partitioning strategy. The shared/assets/landing_zone.py module maintains a centralized registry of asset keys, enabling type-safe cross-project references:

ELEVATION_DSM = AssetKey(["elevation", "dsm"]) ELEVATION_DTM = AssetKey(["elevation", "dtm"]) FORECAST_GRIB_RAW = AssetKey(["forecast", "grib", "raw"]) CLIMATIC_INDICES_CATCHMENT = AssetKey(["climatic_indices", "catchment"])

Dependencies between assets express both data flow and materialization order. The converted elevation tiles asset explicitly declares its dependency on raw tiles through the ins parameter, ensuring Dagster's asset graph correctly represents the relationship and prevents stale data from propagating downstream.

We employ Dagster's component pattern for assets that share structural similarities but operate on different data. The elevation pipeline defines Converted as a component that can be instantiated for both DTM and DSM processing, sharing conversion logic while maintaining separate asset keys and partition spaces.

Partitioning Strategy

Partitioning serves two purposes: it bounds the scope of individual materializations to manageable sizes, and it enables incremental updates without full recomputation. We use different partitioning strategies depending on the data's natural structure.

Elevation data partitions spatially by tile grid and region. A MultiPartitionsDefinition combines a tile index dimension with a regional dimension, allowing selective materialization of specific geographic areas. Dynamic partition definitions enable the tile catalog to grow without code changes-sensors read from index parquet files and issue AddDynamicPartitionsRequest calls to register new partitions.

Satellite imagery partitions temporally using year and month dimensions:

def get_multipartitions_def(self) -> dg.MultiPartitionsDefinition: return dg.MultiPartitionsDefinition({ "index": self.indices_partition, "region": self.regions_partition, })

New temporal partitions register automatically through a sensor that monitors the catalog file for previously unseen year/month combinations.

Meteorological observations partition by data source and processing stage rather than by time. Then pipeline uses a sync-plan/execute-plan pattern where a planning asset determines which source files need synchronization, and an execution asset processes only the delta. This approach handles the irregular update patterns of governmental data sources more gracefully than fixed temporal partitions.

Raster Processing Pipeline

The raster processing subsystem converts heterogeneous input formats into standardized COGs suitable for ML feature extraction. A dedicated module provides the core transformation utilities, built on GDAL and Rasterio.

The main COG writing function orchestrates the complete transformation: coordinate reprojection, resolution resampling, nodata gap filling, geometry clipping, and overview generation. Memory management is critical—we process large rasters block-wise to avoid loading entire datasets into RAM:

def _fill_nodata_gaps( dataset: DatasetWriter, max_search_distance: float, smoothing_iterations: int, ) -> None: """Fill nodata gaps block-wise to avoid loading the whole raster into memory.""" for _, window in dataset.block_windows(1): block = dataset.read(1, window=window, masked=True) if not np.ma.is_masked(block) or not block.mask.any(): continue mask = np.asarray(~block.mask).astype(np.uint8) filled = fillnodata( block.filled(fill_value=dataset.nodata), mask=mask, max_search_distance=max_search_distance, smoothing_iterations=smoothing_iterations, ) dataset.write(np.asarray(filled, dtype=block.dtype), 1, window=window)

Format-specific converters handle the idiosyncrasies of source data. The XYZ converter detects axis ordering issues in point cloud data, the ASCII grid converter parses ESRI's legacy format, and the VRT builder creates virtual rasters for multi-file operations. Each converter produces consistent metadata that downstream assets can rely on.

For smaller rasters below a configurable threshold, we process entirely in memory using Rasterio's MemoryFile. Larger rasters write to temporary files before final COG copy to S3 via GDAL's /vsis3/ virtual filesystem driver. This dual-path approach optimizes for both small-tile throughput and large-raster memory safety.

Data Quality as Dependencies

Data quality checks execute as first-class Dagster asset checks, not as afterthoughts in logging statements. The climatic indices pipeline defines sixteen distinct checks covering structural integrity, range validation, and business logic constraints:

@dg.multi_asset_check( specs=[ dg.AssetCheckSpec("non_empty_data", asset=CLIMATIC_INDICES_CATCHMENT), dg.AssetCheckSpec("primary_key_uniqueness", asset=CLIMATIC_INDICES_CATCHMENT), dg.AssetCheckSpec("pet_avg_valid_range", asset=CLIMATIC_INDICES_CATCHMENT), dg.AssetCheckSpec("aridity_index_avg_valid_range", asset=CLIMATIC_INDICES_CATCHMENT), # ... additional checks ], name="catchment_climatic_indices_checks", ) def _catchment_climatic_indices_checks( context: dg.AssetCheckExecutionContext, duckdb: DuckDBResourceExtended ) -> Iterable[dg.AssetCheckResult]: # Checks execute SQL against DuckDB, returning structured results

Checks validate domain-specific constraints: potential evapotranspiration must fall within 0-15 mm/day, aridity indices between 0-5, precipitation seasonality between -1 and +1. Each check returns structured metadata-not just pass/fail, but the actual values found, enabling rapid diagnosis when checks fail.

A helper function loads the asset's parquet file into a DuckDB temporary table, enabling SQL-based validation without loading the entire dataset into Python memory. This pattern scales to multi-million row datasets while keeping check execution times reasonable.

Geometry validation occurs inline during raster conversion. A dedicated validation function compares source and destination bounds, skipping tiles where reprojection would introduce unacceptable distortion. Rather than failing the entire partition, we record skipped tiles with explicit reasons, allowing manual review of edge cases.

Execution and Elasticity

The platform runs locally for development using uv run dg dev and deploys to Kubernetes for production workloads. Resource requirements vary dramatically across asset types-a metadata sync might need 256MB of memory, while elevation tile conversion demands 16GB.

We express resource requirements through operation tags that map to Kubernetes node pools:

class K8sOpTags: @staticmethod def xlarge() -> dict[str, Any]: return K8sOpTags._config(Nodes.M6I_2XLARGE, divider=2) @staticmethod def gpu() -> dict[str, Any]: return K8sOpTags._config(Nodes.G4DN_2XLARGE, divider=1)

The divider parameter enables fractional node allocation-running two medium workloads on a single large instance, or dedicating an entire GPU node to model training. Assets declare their requirements via op_tags=K8sOpTags.xlarge(), and the Kubernetes executor schedules pods accordingly.

Concurrent processing within assets uses a custom worker pool implementation that handles the messy realities of I/O-bound geospatial work: network timeouts, partial failures, and graceful cancellation. The worker pool provides retry policies, progress logging, and fail-fast behavior while aggregating per-item metrics:

result = worker_pool.process( items=tiles, worker=worker, logger=context.log, max_workers=self.max_workers, cancellation_event=cancellation_event, metrics_extractor=lambda res: { size_key: int(res.metadata.get(size_key, 0)), }, ) result.raise_if_failures()

The worker pool tracks success, failure, skip, and cancellation states for each item, building aggregate statistics that appear in Dagster's materialization metadata. When processing fails partway through, we know exactly which items succeeded and which need retry.

Observability and Lineage

Every asset materialization records structured metadata: row counts for tabular data, dimensions and CRS for rasters, processing duration, and custom metrics like total bytes written. The custom IO manager automatically captures table schemas and row counts; raster assets explicitly record resolution, bounds, and file sizes.

Sensors provide the observability layer for external data sources. The satellite data partition sensor polls catalog files every 30 seconds, logging new partition discoveries and registration requests. Forecast schedules run four times daily at fixed UTC times, with run keys that encode the scheduled timestamp for easy identification:

@dg.schedule( cron_schedule="30 8,13,16,20 * * *", target=dg.AssetSelection.assets(FORECAST_GRIB_RAW), ) def forecast_grib_raw_schedule(context: dg.ScheduleEvaluationContext) -> dg.RunRequest: scheduled_time = context.scheduled_execution_time return dg.RunRequest( run_key=f"forecast_grib_raw_{scheduled_time.strftime('%Y%m%d_%H%M')}", tags={"schedule": "forecast_grib_raw"}, )

The declarative automation condition enables declarative freshness policies-assets can specify how stale they're allowed to become, and Dagster automatically triggers materializations to maintain freshness. We use this for assets that need to stay current with upstream changes without manual intervention.

Asset lineage flows automatically from dependency declarations. When investigating a model prediction, we can trace from the model asset back through training data, through climatic indices, through individual station observations, to the original source files. This lineage persists across runs, enabling historical comparisons when methodology changes.

Lessons from Production: Architectural Revisions

Three architectural decisions required significant revision after initial deployment.

First, we underestimated the memory requirements for raster operations. Early implementations loaded entire tiles into memory, which worked fine for small test datasets but caused OOM kills on production-scale elevation models. The fix required systematic refactoring to block-wise processing throughout the raster pipeline-reading, transforming, and writing in chunks that fit within pod memory limits. This added complexity but eliminated an entire class of production incidents.

Second, we initially implemented dynamic partitions without proper cleanup logic. Sensors would happily add new partitions as data arrived, but nothing removed partitions for data that had been superseded or corrected. Over time, the partition space accumulated stale entries that confused operators and wasted storage. We added explicit partition lifecycle management: sensors now compare desired partitions against current state and issue both AddDynamicPartitionsRequest and DeleteDynamicPartitionsRequest as needed.

Third, we placed too much validation logic inside asset compute functions rather than as separate asset checks. This made debugging failures difficult-a validation error would fail the entire materialization, losing the partial work already completed. Extracting validation into dedicated asset checks with structured metadata output dramatically improved debuggability and allowed us to materialize "known-bad" data when necessary for investigation, running checks separately.

Open Questions and Next Steps

Several architectural questions remain unresolved in the current implementation.

The platform lacks a unified approach to schema evolution. When upstream data sources change their formats-which governmental APIs do without warning-we currently handle it through ad-hoc converter updates. A more systematic approach might involve schema registries or versioned asset definitions, but the right pattern for geospatial data with complex nested structures remains unclear.

Cross-project asset dependencies work through shared asset key definitions, but the materialization coordination relies on manual scheduling or external triggers. A more elegant solution might use Dagster's cross-code-location asset dependencies, but this would require restructuring how projects deploy and discover each other's assets.